Introduction to Docker

A step-by-step guide to deploying your first container and beyond.

Tuesday, November 11, 2025

14 minute read

Introduction

This workshop is a group project created for the course COMP SCI 502, Theory and Practice of Computer Science Education, at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In this workshop, you will learn to run programs inside containers using a platform called Docker. Docker allows developers to package applications and their dependencies into lightweight, portable containers. Think of a container as a standardized unit that includes everything needed to run a piece of software: the code, runtime, system tools, libraries, and settings.

The main benefit of Docker is that it solves the classic “it works on my machine” problem by effectively shipping the machine alongside the program. A containerized application will run the same way whether it’s on your laptop, a friend’s computer, or a production server, because the container includes the entire environment the application needs. While they have a lot in common with virtual machines, Docker containers are different: VMs include an entire operating system, but containers share a kernel with the host system. This makes containers much more lightweight and faster to start up, and you can run many containers on a single machine without the overhead of multiple full operating systems.

Developers use Docker for various purposes: ensuring consistency across development and production environments, simplifying deployment, making it easier to scale applications, and isolating different applications from each other. It’s become a foundational technology in modern software development, particularly in microservices architectures and cloud computing.

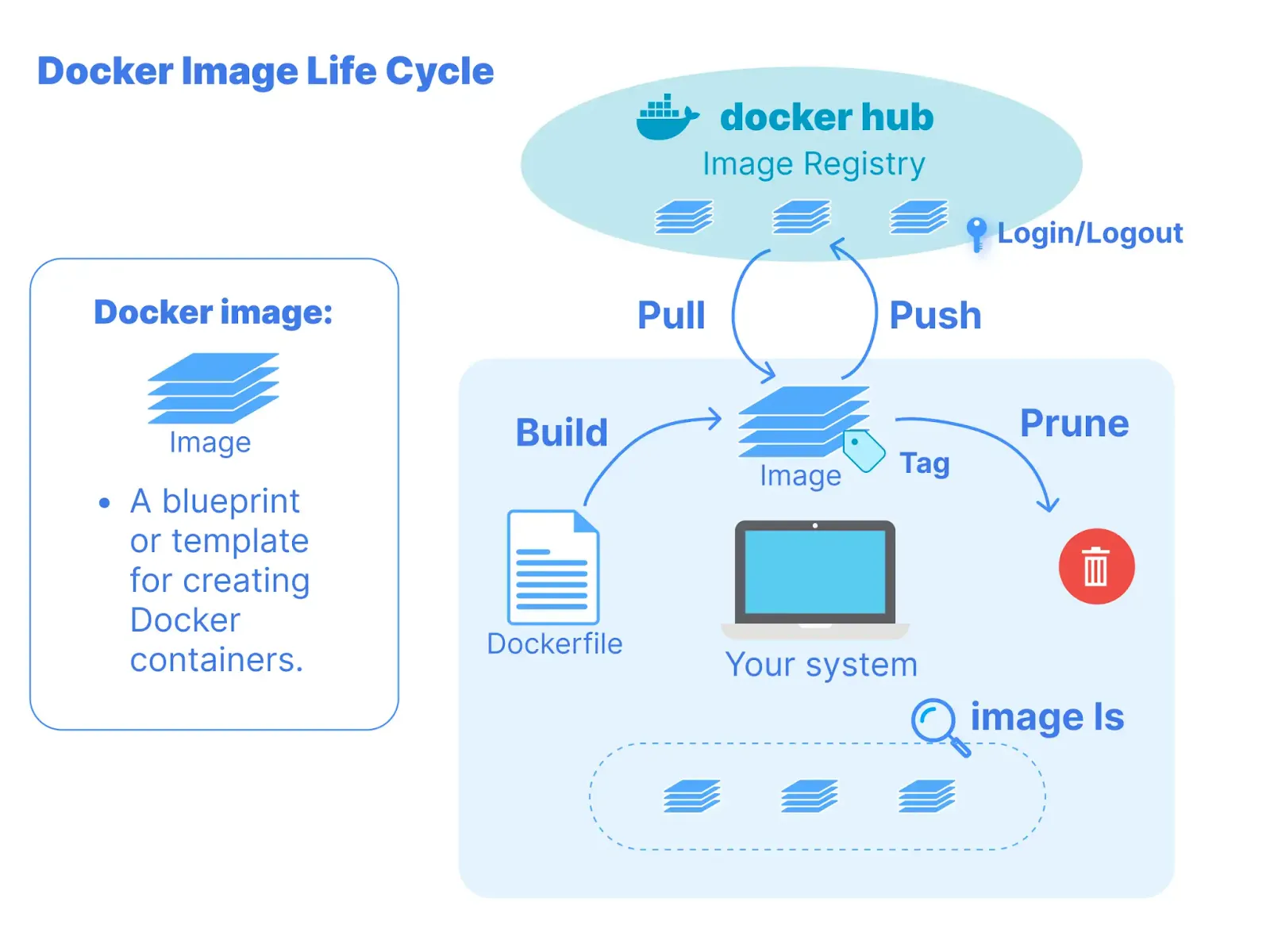

The basic workflow involves writing a Dockerfile (which specifies how to build your container), building an image from that file, and then running containers from that image. Images can be shared through Docker Hub or other container registries, making it easy to distribute applications.

Why should I use Docker?

Pros

- Reproducibility (same image ⇒ same environment)

An image freezes your userspace: OS base, packages, config, and entrypoint. If everyone runsdocker run myteam/app:1.3, you all get identical behavior. - Fast startup & low overhead (share the host kernel)

Containers don’t boot a full OS; the process starts almost immediately, so iteration is quick. Compared to VMs, you use less RAM/CPU and can run many containers side-by-side. - Strong isolation with easy reset (safe to break things)

If you break a container (evenrm -rf /inside it), you can remove and recreate it in seconds from the image. This makes experimentation low-risk for execution. - Infrastructure-as-code with Dockerfiles.

A Dockerfile documents setup steps (FROM, RUN, COPY, CMD) so your environment is auditable and diff-able in Git. Builds are deterministic, and you can refactor layers for speed. - Composable with Linux tooling you already know

Because it’s just a process, you can use the standard docker command to manage it, and because the docker command is composable, you can inspect withps, manage with signals (docker kill→ KILL), watch I/O/CPU withtime/htop, storage withdf -h/du -sh, and listeners withss -tulpn. Or pipe (|) its text output to other Linux tools like grep to easily filter, automate, and script anything you need.

Cons

- Kernel dependency (Linux containers need a Linux kernel)

On Windows/macOS, Docker runs a lightweight VM to provide a Linux kernel. That layer can introduce file-sharing inconsistencies and path differences. - Networking & ports can be confusing at first

Processes inside containers listen on container IPs; you must publish ports to reach them. When something “isn’t reachable,” checkdocker logs,docker exec -it <ctr> ss -tulpn, and confirm the app bound to0.0.0.0not127.0.0.1 - Excessive disk usage from layers, caches, and container

Builds and pulls accumulate layers, exited containers and dangling images silently consume GBs. - Your responsibility for managing container resources

A single runaway container can exhaust CPU/RAM. Use--cpus,--memory, anddocker statsto cap usage, and prefer streaming/pipelines to reduce memory pressure. Remember: your VM may be over-booked.

Deploying your first container

- Install docker

curl -fsSL https://get.docker.com -o get-docker.sh

sudo sh get-docker.sh

sudo usermod -aG docker $USER # Add yourself to docker group

# Log out and back in for group changes to take effect- Write your first Dockerfile

FROM python:3.12-slim # Base image (your starting point)

WORKDIR /app # Set working directory inside container

COPY app.py .

RUN pip install flask # Execute commands during build (installs dependencies)

CMD ["python", "app.py"] # Default command when container starts- Build and run

docker build -t my-first-app .

docker run -p 8080:5000 my-first-app- Boom

Now let’s see you give it a try yourself!

Challenge 1: Base Image

Start with a base image. Use the FROM instruction to specify node:18-alpine as your base image.

What’s the difference between an image and a container?

A Docker image is like a blueprint or template. It’s a read-only package that contains everything needed to run an application: the code, runtime, libraries, environment variables, and configuration files. Think of it as a snapshot of a filesystem at a specific point in time. Images are built from Dockerfiles and stored either locally or in registries like Docker Hub.

A container, on the other hand, is a running instance of an image. It’s what you get when you execute docker run on an image. While the image is static and immutable, a container is dynamic. The container has its own writable layer on top of the image where changes can be made during runtime. You can create multiple containers from the same image, and each will run independently with its own state. Unless you commit it to create a new image or use volumes, any changes made to the container’s filesystem will be lost when the container is removed. The writable layer exists as long as the container exists (even when stopped), but once you run docker rm to remove the container, all those changes disappear.

For databases and other stateful applications in Docker, always use volumes to persist data beyond the container’s lifecycle!

The core idea is:

An image is a read-only, versioned template (the recipe), it’s stateless.

A container is a running (or stopped) instance created from an image (the meal), it has state.

If I edit files inside a running container, does that change the image?

No. The image stays read-only; your edits live in the container’s writable layer and won’t be transferred to a new container made from the same image. If you edit files in an attached volume or bind mount, your changes will be persisted after the container is deleted.

Here’s a small interactive demo to visualize images and containers. You can “create an image” by building it, then “run containers” from that image or delete the image. All of these operations correspond to real Docker commands you would run in your terminal, which you’ll learn about in the Commands to use and manage Docker section below.

Dockerfile

FROM node:18-alpine WORKDIR /app COPY package.json . RUN npm install COPY . . CMD ["node", "index.js"]

Images

No images built yet

Containers

No containers running

Tip: Click Build to create an image from the Dockerfile.

Click Run on an image to start a container. Hover over items to see actions.

Understanding Image Layers

A Docker image is actually made up of many layers stacked on top of each other. Each instruction in a Dockerfile creates a new layer in the final image. This layered architecture is one of Docker’s key innovations that makes it efficient.

When Docker builds an image, it executes each Dockerfile instruction in sequence:

- Each RUN, COPY, ADD instruction creates a new layer

- Layers are read-only and cached

- If you rebuild an image and a layer hasn’t changed, Docker reuses the cached version

For example, consider this Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu:latest # Layer 1: Base image

WORKDIR /workspace # Layer 2: Change work directory

RUN apt-get update && apt install … # Layer 3: Install environment

COPY . . # Layer 4: Copy local files

RUN make -j # Layer 5: Build command

CMD ["make", "run"] # Layer 6: Run the program, metadata (no size)If you only change your application code, Docker can reuse the cached layers 1-3 and only rebuild from layer 4 onward. This makes builds much faster! However, if you switch Layer 3 and Layer 4, because your code base has changed, starting from the changed layer, everything has to be built again. That’s why people would move layers that won’t change too often to the top of the Dockerfile.

Optimizing Dockerfile order

Order your Dockerfile instructions from least to most frequently changed. Put dependency installation before copying source code, since code changes more often than dependencies.

Also, you can inspect how an image was built using docker history <image>. However, do note that if you commit a layer, you won’t see how that layer is built… So, try not to use the commit command too often, especially for production.

Commands to use and manage Docker

[!information] Docker group and debugging notes

You shouldn’t needsudoif your user is in the docker group. You can add yourself to this group (on Debian or Ubuntu) by runningsudo usermod -aG docker $USERIf a run “does nothing,” you likely forgot to supply a command (e.g., bash) or the program exits immediately. To see more information, use

-itor checkdocker logs.

Pull images

What it does: Downloads a snapshot of installed software (an image) from a registry (e.g., Docker Hub) onto your VM.

Why first: You run containers from images. No image → nothing to run.

Core commands

docker pull ubuntu:24.04 # fetch a specific tag/version

docker images # list images you have

docker tag ubuntu:24.04 my-ubuntu:lts # add a convenient name for the same imageDocker pull auto-retrieval

If docker run references an image you don’t have, Docker will try to pull it automatically. Failures like “repository does not exist or may require ‘docker login’” are usually a typo in the image name, not an auth problem.

Build images

What it does: Creates your own image by executing scripted install steps inside a temporary build container, then snapshotting the result.

Why: Reproducibility. Everyone else can build/get the identical environment instead of “works on my machine.”

Minimal Dockerfile

FROM ubuntu:22.04

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y python3-pip

RUN pip3 install pandas

CMD ["bash"] # default program when a container startsBuild it

# build in the current directory (where Dockerfile lives)

docker build -t pandas .Quick check

docker images | grep pandasRun containers (from images)

What it does: Starts an isolated Linux sandbox where your processes run

Interactive shell

docker run -it ubuntu:25.10 bashQuick check

docker run ubuntu:25.10 echo "hello"Inspect and troubleshoot

docker ps # running containers

docker ps -a # include exited

docker logs mybox # show logs (add -f to follow)

docker exec -it mybox bash # jump into a running container

docker stop mybox # graceful (SIGTERM then SIGKILL)

docker kill mybox # force (SIGKILL)

docker rm mybox # remove stopped containerImage as class pattern

Think “class → objects”: image is the class; each docker run makes a new object (container).

Use -it for interactive programs; -d for background jobs.

Clean up exited containers periodically (docker rm $(docker ps -aq)), especially when disk fills up.

Compose

What it does: Defines and runs multi-container apps (e.g., web + db) via a single YAML file.

Read more in the Docker Compose section below.

services:

app:

image: python:3.12

command: python -m http.server 8000

ports: ['8000:8000']Quick Check

docker compose up -d # start

docker compose ps # status

docker compose logs -f # follow logs

docker compose down # stop & removeHere’s a playground terminal for you to try out Docker commands:

Try: docker images, docker ps, docker build -t my-app .

Use ↑/↓ arrows for command history

Docker Compose

Docker Compose is a tool for defining and running multi-container applications in a declarative way. Instead of memorizing and typing out long docker run commands with all their flags and options, you write a single YAML file that describes your entire container setup, and Compose handles spinning everything up for you. You describe what you want, and Compose figures out how to make it happen. Even better, it handles things like creating networks automatically, ensuring services can find each other by name, and managing the startup order when services depend on each other.

Try it yourself! This interactive converter lets you switch between Docker Compose and docker run formats. Type in either editor to see the conversion in real-time:

Some directives like build: ./api or depends_on: in the advanced example are Compose-specific and don’t have direct docker run equivalents. Compose handles build context, networks, and dependencies for you behind the scenes!

If you wanted to replicate those manually, you’d need to run docker build separately for the build context, and wait to start dependent containers until their dependencies are healthy.

Services can reference each other by their service name. Inside the api container, you can connect to database:5432 rather than having to figure out IP addresses or worry about what network they’re on. Compose creates a dedicated network for this application automatically.

Here are some useful Compose commands:

- You can bring everything up with

docker compose up -d, which starts all services in the background. The-dflag means detached mode, like with regular Docker. - To see what’s running, use

docker compose ps. This shows you all the services in your application and their status. You can get the logs from all containers withdocker compose logs -f, or just one service fromdocker compose logs -f api - When you need to rebuild your images after code changes,

docker compose up --buildwill rebuild and restart any services that have changed. And when you’re done,docker compose downstops and removes all containers, networks, and optionally volumes with the-vflag.

Docker Compose isn’t meant for production orchestration at scale (that’s where Kubernetes or Docker Swarm come in), but for development, testing, and simple deployments on a single host, it’s an incredibly practical tool that eliminates a huge amount of manual coordination and makes your infrastructure reproducible and shareable.

Integrating with Developer Tools

This is my favorite topic to talk about, as these are the ways that I use Docker a lot.

Docker integrates seamlessly with modern development workflows, making it easier to maintain consistent environments across your entire team and CI/CD pipeline.

The key advantage of integrating with developer tools is that they eliminate the “works on my machine” problem. Whether you’re coding locally, pushing to CI, or deploying to production, the same Docker image ensures consistency across all environments.

Let’s look at some examples.

VS Code Integration

If you’re sick of typing the docker command, we recommend you to install two VS Code extensions: Container Tools and Docker DX.

Container Tools (by Microsoft) adds a visual interface to manage containers, images, and volumes directly from VS Code. You can pull images, run containers, view logs, attach a terminal, and even attach VS Code (so that you don’t have to forward some ports to ssh into the container). It’s perfect for managing and debugging containers.

Docker DX (by Docker) focuses on authoring. It provides smart IntelliSense, syntax highlighting, and best-practice hints for Dockerfiles, Compose, and Bake files. It can even surface build warnings and vulnerabilities inline while you write.

As of publishing, it’s an extension pack that contains a single extension, making it effectively another way to download Container Tools. So, for the best experience, it’s recommended to install Container Tools and Docker DX separately.

Dev Container (and Codespaces)

If you’ve ever cloned a project, spent half an hour setting up dependencies, and then discovered “it works on my machine but not yours,” Dev Containers are here to save you.

A Dev Container is basically a Docker-powered development environment defined by a simple config file (.devcontainer/devcontainer.json). It tells VS Code what image to use, which extensions to install, and how to set up the workspace.

You just open the folder in VS Code, and it automatically builds and launches the containerized environment. From your perspective, it feels like you’re coding on your local machine, but in fact, everything runs inside the container. That means your dependencies, compilers, and runtimes are all isolated and reproducible.

Codespaces takes this one step further. It’s the same idea as Dev Containers, but hosted in the cloud by GitHub. Instead of building locally, Codespaces spins up your container on a remote VM, preloaded with your code and environment. You can connect to it from VS Code or even use it straight in the browser. This is perfect for quick edits, demos, or when your laptop fan sounds like it’s about to take off.

Here is an example of devcontainer.json:

{

"name": "Example Dev Container",

"image": "mcr.microsoft.com/devcontainers/javascript-node:22",

"features": {

"ghcr.io/devcontainers/features/git:1": {}

},

"forwardPorts": [3000, 5000, 5173],

"postCreateCommand": "npm --version && node --version",

"customizations": {

"vscode": {

"extensions": ["dbaeumer.vscode-eslint", "esbenp.prettier-vscode"],

"settings": {

"editor.rulers": [120],

"editor.formatOnSave": true,

"editor.tabSize": 4

}

}

}

}Approach 1:

docker network create myapp-network

# Start database

docker run -d \

--name db \

--network myapp-network \

postgres:15

# Start web app

docker run -d \

--name web \

--network myapp-network \

-p 8080:8080 \

-e DATABASE_URL=postgresql://db:5432/mydb \

My-web-app # Then communicate use container name as host nameApproach 2: Docker Compose

- Create

docker-compose.yamlfile:

services:

database:

image: postgres:15

environment:

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: secret

web:

build: .

ports:

- "8080:8080"

environment:

DATABASE_URL: postgresql://database:5432/mydb

depends_on:

- database- Run

docker compose up -d- Then each container can communicate with another using host name and docker will automatically resolve it to the correct IP address